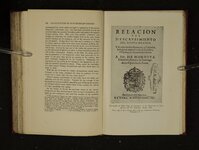

| Title |

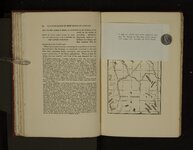

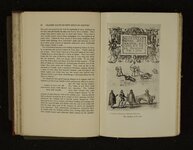

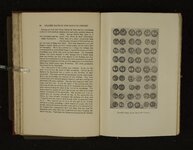

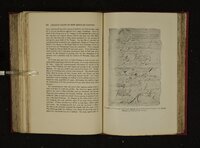

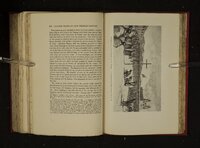

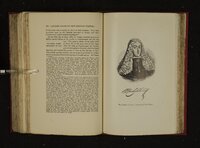

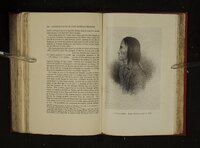

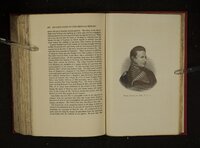

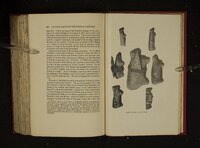

Leading facts of New Mexican history, volume 1 |

| Call Number |

F796 .T97 1911a v.1 |

| Date |

1911 |

| Description |

Volume 1 of a 5-volume set. Copy number 1464 of 1500 autograph copies. Considered the first major history of the state, "The leading facts" was published on the eve of New Mexico attaining statehood in 1912. Its author, Ralph Emerson Twitchell had arrived in the early 1880s and served in the territorial militia, and was mayor of Santa Fe and served as district attorney of Santa Fe County. He did much to promote the progress of the territory and its elevation to statehood. |

| Creator |

Twitchell, Ralph Emerson, 1859-1925 |

| Subject |

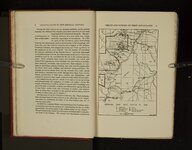

New Mexico--History; New Mexico--Biography |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Spatial Coverage |

New Mexico, United States |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6vq92cp |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

1701788 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6vq92cp |