| Title |

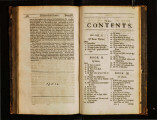

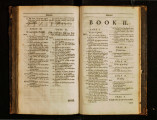

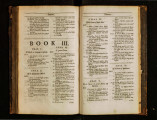

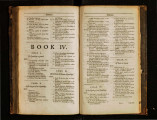

Essay Concerning Human Understanding |

| Call Number |

B1290 1831; Record ID 995911070102001 |

| Date |

1690 |

| Description |

Locke, John (1632-1704). An essay concerning humane understanding. London: Printed by Elizabeth Holt for Thomas Basset, 1690 First edition, first issue B1290 1690 University of Utah copy bound in contemporary paneled calf |

| Creator |

John Locke (1632-1704) |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Knowledge, Theory of |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 600 ppi tiffs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6j409sw |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

293145 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6j409sw |