| Title |

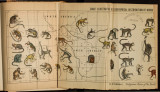

Indigenous Races of the Earth |

| Call Number |

GN23 .N88 1857; Record ID 991665020102001 |

| Date |

1857 |

| Description |

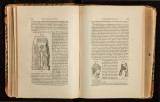

Nott, Josiah Clark (1804-1873). Indigenous races of the earth; or, new chapters of...Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1857 First edition, subscriber's copy GN23 N88 1857 |

| Creator |

Josiah Clark Nott (1804-1873) |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Acclimatization; Craniology; Ethnic groups -- Pictorial works; Ethnology; Giddon, Goerge R. (George Robins), 1809-1857); Language and languages; Maury, Louis Ferdinand Alfred, 1817-1892; Meigs, James Aitken, 1829-1879; Monkeys; Monogenism and polygenism; Pulszky, Ferencz Aurelius, 1814-1897 |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XGN23N881857.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tifs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page PDF. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s61p18sq |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

281487 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s61p18sq |