| OCR Text |

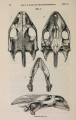

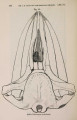

Show 1873.] MR. R. B. SHARPE ON FALCO ARCTICUS, 417 plumage by the exact sequence of change followed by another allied species. There can be no doubt that when we thoroughly understand the changes of plumage undergone by species of birds, a new light will be thrown upon ornithology as regards the relation of geographical races and subspecies. In treating of the Greenland Falcon, one difficulty always pre* sents itself; and that is, the almost impossible chance of getting specimens correctly sexed and dated ; and in a study of this kind this is half the battle. To capture a specimen, and watch the gradual changes in confinement, would doubtless afford some clue; but the species under consideration would be an unsuitable one for experiment, as there can be little doubt that confinement in England would produce more or less the consequences of arrested development in the plumage, by destroying the need of assimilative colouring which induces the species to become white in the regions it inhabits. Fig. 2 represents the centre tail-feather of the bird from whose back I took the first feather (fig. 1); and it will be noticed that the lower bars give traces of approaching dissolution. The way in which this takes place is well illustrated in fig. 3, which is the tail-feather of a slightly older bird. Fig. 4 represents the back of a young bird changing from its first into its second plumage: x is the old feather, very similar to fig. 1 ; and the darker feathers are the new ones being donned. Fig. 3 is the middle tail-feather of this identical specimen ; and thus it appears that the commencement of the great change of tail takes place about the time of the first moult. Fig. 5 is a feather taken from a bird not yet fully adult, but in full clean-moulted plumage; it has a tail in the same stage as fig. .**', and is doubtless very little older than the specimen whose tail is thus represented in the Plate: in fact it is in the full plumage indicated by the new feathers (fig. 4), and shows its slightly advanced age by the greater extent of the white indent. The step from this stage of the dorsal feathers to tbe next (fig. 6) is tolerably evident; for here the bars, indicated in the previous stages, are quite complete. A bird thus marked is the adult of the "dark race" of Mr. Gould, which we have thus followed from its young to its perfect plumage. It will perhaps render my argument more intelligible if, for the present, we leave aside the feathers represented in figs. 7, 7 a, and 8, and proceed atonce to the consideration of the so-called "light race" of F. candicans. It is a remarkable fact that, although there exists great difference in the tail-feathers in the dark race, the light form should have the tail nearly uniform white in both young and old. Thus figs. 9, 9 a are taken from the back of a bird in the " tear-dropped " plumage, which is supposed to be the young, and figs. 10, 10 a, 12, 12«, are all from the backs of very old birds. With this last fact I perfectly agree; but so far from considering the feathers figured as 9, 9 a to be those of a young bird, I consider that they are the sign of a very old specimen, only one whit less old than the one from whose back the feathers figs. 10 and 10 a have been drawn. The PROC. ZOOL. Soc-1873, No. XXVII. 27 |