| OCR Text |

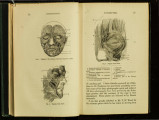

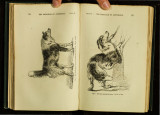

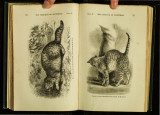

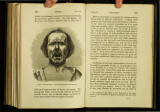

Show 364 CONCLUDING REMARKS CHAP. XIV. exhibited by a widely open mouth; but the eyes :voulcl have been opened and the eyebrows arched. J?Isgust would have been shown at a very early penod by movements round the mouth, like those of vomiting, -that is, if the view which I have suggested respecting the source of the expression is correct, namely, that our progenitors had the power, and used it, of volu~tarily · and quickly rejecting any food from thmr stomachs which they disliked. But the more refined manner of showing contempt or disdain, by lowering the eyelids, or turning away the eyes and face, as if the despised person were not worth looking at, would not probably have been acquired until a much later period. Of all expressions, blushing seems to be the most strictly human; yet it is common to all or nearly all the races of 1nan, whether or not any change of colour is visible in their skin. The relaxation of the small arteries of the surface, on which blushing depends, seems to have primarily resulted from earnest attention directed to the appearance of our own persons, especially of our faces, aided by habit, inheritance, and the ready flow of nerve-force along accustomed channels; and afterwards to have been extended by the power of association to self-attention directed to moral conduct. It can hardly be doubted that many animals are ~apable of appreciating beautiful colours and even forn1s, as is shown by the pains which the individuals of one sex take in displaying their beauty before those of the opposite sex. But it does not seem possible that any animal, until its mental powers had been developed to an equal or nearly equal degree with those of man, would have closely considered and been sensitive about its own personal appearance. Therefore we rna~ co~clude that blushing originated at a very late perwd m the long line of our descent. CHAP. XIV. AND SUMMARY. 365 From the various facts just alluded to, and given in the course of this volume, it follows that, if the structt~ re of ?ur organs of respiration and circulation had differed In only a slight degree from the state in which they now exist, most of our expres ions would have been wonderfully differ~nt. A v~ry slight change in the course of the artenes and ve1ns which run to the head would probably have prevented the blood from accu~ mulati.ng in ou: eyeballs during viol nt expiration; for this occuTs In extr mely few quadrupeds. In this case we should not have djsplay d some of our most characteristic expressions. If man had breathed water by the aid of external branchiro (though the idea is hardly conceivable), instead of air through his mouth and. nostrils, his features would not have ex pres ed his feel1ngs much more efficiently than now do his hands or limbs. Rage and disgust, however, would still have been shown by movements about the lips and mouth, and the eyes would have become brighter or duller according to the state of the circulation. If our ears had remained movable, their movements would have been highly expressive, as is the case with all the ~nimals which fight with their teeth ; and we may ln.fer that our early progenitors thus fought, as we still uncover the canine tooth on one side when we sneer at or defy any one, and we uncover all our teeth when furiously enraged. The move~en~s _of expression in the face and body, whatever their ong1n may have been, are in themselves of much importance for our welfare. They serve as the first means of communication b tw en the mother and be~ infant; sh.e smiles approval, and thus encourages her ?hild on ~he nght path, or frowns disapproval. We read1ly perceive sympathy in others by their expres- |