| Title |

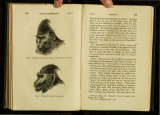

Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals |

| Call Number |

QP401 .D3; Record ID 99335160102001 |

| Date |

1872 |

| Description |

Darwin, Charles (1809-1882). The expression of the emotions in man and animal. London: J. Murray, 1872 First edition QP401 D3 Edition of seven thousand copies. |

| Creator |

Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Emotions; Instinct; Psychology, Comparative |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XQP401D3.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tifs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page PDF. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6s21b6j |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

282029 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6s21b6j |