| Title |

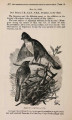

Proceedings of the General Meetings for Scientific Business of the Zoological Society of London 1892 |

| Call Number |

QL1 .Z7; Record ID 997682580102001 |

| Date |

1892 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Zoology; Periodicals |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Jason VanCott |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned on Kirtas 2400 with Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II, 16.7 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi uncompressed TIFF, 16 bit depth. Display image generated in Kirtas Technologies' OCR Manager as multiple page PDF. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6t75s4k |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

262670 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6t75s4k |