| OCR Text |

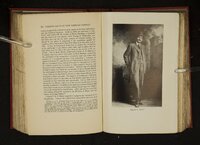

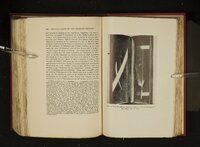

Show MANNERS AND CUSTOMS OF THE PEOPLE 161 the Indian tombé was in evidence. The leader of the orchestra was called the maestro, and the master of the ceremonies of the baile was known as the bastonero, the latter carrying a small cane, his badge of authority. Sitting on the platform with the musicos was an individual with more or less ability at impromptu versification, and during the progress of the festivities of the evening this important personage would delight the assembled audience with more or less choice ebullitions of native wit, directed almost invariably to the persons of consequence or notoriety who happened to be present and whose personality suggested to this humble poet occasional brilliant sallies in verse, to the confusion of the person mentioned, and to the infinite joy of the dancers and spectators, and always to the satisfaction of the versifier. No invitations were extended to these affairs, except in the evening after sun-down the musicos were accustomed to parade around the public plaza, all the while performing upon their instruments; this was the gallo, or notice of the baile. Arriving at the place where the baile was to be held, the spectators would take seats on both sides of the sala. The young ladies were invariably accompanied by their mothers or some other lady relative or intimate friend of the family. It was never the custom, as in the ‘‘states,’’ to have the sets called by a ‘‘caller,’’ dancing in all its forms being too well known to every Mexican, young or old, although some of the Spanish cotillions were very complicated. The bastonero had full charge of everything connected with the dance, and when the spectators and dancers were very numerous it was his duty, always well performed, to select the men who would take part in any dance, they, of course, selecting their own partners. The ordinary waltz was known as the valse redondo, but the dances par excellence were the cwna and the valse despacio. In the elethe but mournful, somewhat and slow is music the named last gant movement is difficult to describe. In the one, the first figure might be called a sort of ‘‘waltz quadrille,’’ ending with two lines, each sefiorita facing her partner. Thence she would advance toward him, with graceful gesture, bowing, sinking, rising, extending hands and again clasping them and retreating, waving scarf or handkerchief, all in perfect time and without faulty or ungraceful |