| Title |

Island Life: or, The Phenomena and Causes of Insular... |

| Call Number |

QH85 .W18 1880; Record ID 992256390102001 |

| Date |

1880 |

| Description |

Island life: or, the phenomena and causes of insular...London: Macmillan, 1880 First edition QH85 W18 1800 |

| Creator |

Wallace, Alfred Russel, 1823-1913 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

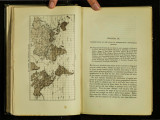

Biogeography; Glacial epoch; Islands; Phytogeography |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XQH85W181880.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tifs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobad ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6477kj1 |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

283306 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6477kj1 |