| OCR Text |

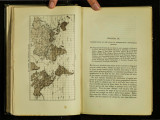

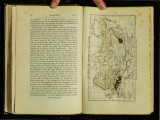

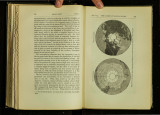

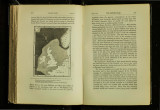

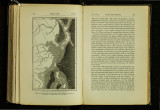

Show ISLAND LIFE. [PART I. 110 ---------------------------- found underneath moraines, drift, and other late glacial deposits, but never overlies them (except in special cases to be hereafter referred to), so that it is certainly an earlier deposit. . . Tbrouahout Scotland where "till" is found, the glae1al stnre, perched blocks, Taches 'mmttonnees, and. other marks of glacial action occur very high up the mountams to at least 3,000 and often ~ven to 3 500 feet above the sea, while all lower bills and mountains are' rounded and grooved on their very summits ; and these grooves always radiate outwards from the highest peaks and ridCTeS towards the valleys or the sea. Inferences f;orn the Glacial Phenomena of. Scotlan~.- Now all these phenomena taken together render 1t certam. that the whole of Scotland was once buried in a vast sea of ICe, out of which only the highest mountains raised their summits. Th~re is absolutely no escape from this conclusion; for the facts whiCh lead to it are not local-found only in one spot or one valley-but general throughout the entire length and breadth of Scotland ; and are besides supported by such a mass of detailed corroborative evidence as to amount to absolute demonstration. The weight of this vast ice-sheet, at least thr~e thousand fe~t in maximum thickness, and continually movmg seaward w1th a slow grinding motion like that of all existing glaciers, must have ground down the whole surface of the country, especially all the prominences, leaving the rounded rocks as well as the grooves and strire we still see marking the direction of its motion. All the loose stones and rock-masses which lay on the surface would be pressed into the ice ; the harder blocks would serve as scratching and grinding tools, and would thus themselves become rounded, scratched and striated as we see them, while all the softer masses would b: ground up into impalpable mud along with ~he material planed off the rocky projections of the country, leavmg them in the condition of roches moutonnees. The peculiar characters of the "till," its fine.ness and .tenacity, correspond closely with the fine matter whiCh .now 1ss:1es from under all glaciers, making the streams m1lky wh1te, vellow or brown, according to the nature of the rock. The ~edim~nt from such water is a fine unctuous sticky deposit, only needing pressure to form it into a tenacious clay ; and CHAP. VII J THE GLACIAL EPOCH. 111 when "till" is exposed to the action of water, it dissolves into a similar soft sticky unctuous mud. The present glaciers of the Al~s, being confined to valleys which carry off a large quantity of drawage water, lose this mud perhaps as rapidly as it is formed; but when the ice covered the whole country, there was comparatively little drainage water, and thus the mud and stones c?llect.ed in vast compact masses in all tbe hollows, and especmlly m the lower flat valleys, so that, when the ice retreated, the whole country was more or less covered with it. It was then, no doubt, rapidly denuded by rain and rivers, but, as we have seen, great quantities remain to the present day to tell the tale of its wonderful formation. 1 There is good evidence that, 1 This view of the formation of "till" is that adopted by Dr. G eikie, and upheld by almost all the Scotch, Swiss, and Scandinavian geoloo·ists. 'l'he objection however is made by many eminent English geolo:.isls including Mr. Searles V. Wood, Jun., that mud ground off the ~uck~ cannot remain beneath the ice, forming sheets of groat thickness becaul: le the glacier cannot at the same time grind down solid roclc 1 and yet pass over the surface of soft mud and loose stones. But this difficulty will disappear if we consider the numerous fluctuations in the glacier with increasing size, and the additions it must have been constantly receiving as the ice from one valley after another joined together, and at last produced an ice-sheet covering the whole country. The grinding power is the motion and pressure of the ice, and the pressure will depend on its thickness. Now the points of maximum thickness must have often changed their positions, and the result would be that the matter ground out in one place would be forced into anotl1er place where the pressure was less. If there were no lateral escape for the mud, it would necessarily support the ice over it just as a water-bed supports the person lying on it; and when there was little drainage water, aud the ice extended, say, twenty miles in every direction from a given part of a valley where the ice was of less than the average thickness, the mud would necessarily accumulate at thi~ part simply because there was no escape for it. Whenever the pressure all round any area was greater than the pressure on that area, the debris of the surronnding parts would be forced into it and would even raise up the ice to give it room. 'This is a necessar; result of hydrostatic pressure. During this process the superfluous water would no doubt escape through fissures or pores of the ice, and would leave the mud and stones in that excessively compressed and tenacious condition in which the " till " is found. 'I' he unequal thickness and pressure of the ice above referred to would be a necessary consequence of the inequalities in the valleyR, now narrowing into gorges, now opening out into wide plains, and again narrowed lower down; and it is just in |