| OCR Text |

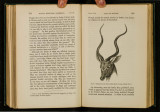

Show I I, 398 GENERAL SUMMARY and such widely separated classes, is intelligible if we admit the action throughout all the higher divisions. of the animal kingdom of one common cause, namely sexual selection. Sexual selection depends on the success of certain individuals over others of tho same sox in relation to· the propagation of the species; whilst natural selection depends on the success of both sexes, at all ages, in relation to the general conditions of lifo. Tho sexual struggle is of two kinds; in tho one it is between the individuals of the same sex, generally the male sex, in order to drive away or kill their rivals, the females remaining passive; whilst in the other, the struggle is likewise between the individuals of the same sex in order to excite or charm those of tho opposite ~ex, generally the females, which no longer remain passive, but select the more agreeable partners. This latter kind of selection is closely analogous to that which man unintentionally, yet effectually, brings to bear on his. domesticated productions, when he continues for a lonotime choosing the most pleasing or useful individual~ without any wish to modify the breed. The laws of inheritance determine whether charac-· tors gained through sexual selection by either sex shall be transmitted to the ~arne sex, or to both sexes; as. well as the age at which they shall be developed. It appears that variations which arise late in life are commonly transmitted to one and the same sex. Variability is the necessary basis for the action of selection and is wholly independent of it. It follows from this' that variations of the same general nature have ofte~ been taken advantage of and accumulated thrm.wh sexu.al selection in relation to the propngation of the species, and through natural selection in relation to the general purposes of life. Hence secondary sexual cha- CHAP. XXI. AND CONCLUDING REMARKS. 399' racters, when equally transmitted to both sexes can be distino-nished from ordinary specific characters only by the li~ht of analogy. The modifications acquired through sexual selection are often so strongly pronounced that the two sexes have frequently been ranked as distinct species, or even as distinct genera. Such stronglymarked differences must be in some manner highly important; and we know that they have been acquired in some instances at the cost not only of inconvenience, but of exposure to actual danger. The belief in tho power of sexual selection rests chiefly on the following considerations. The characters. which we have the best reason for supposing to have been thus acquired are confined to one sex ; and this nlone renders it probable that they are in some way connected with the act of reproduction. These characters in innumerable instances are fully developed only at maturity; and often during only a part of the year, which is always the breeding-season. The males (passing over a few exceptional cases) are tho most active in courtship ; they are the best armed, and are rendered the most attractive in various ways. It is to be especially observed that the males display their attractions with elaborate care in the presence of the females ; and that they rarely or never display them excepting during the season of love. It is incredible that all this display should Lo purposeless. Lastly we have distinct evidence with some quadrupeds and birds that the individuals of the one sex are capable of feeling a strong antipathy or preference for certain individuals of the opposite sex. Bearing these facts in mind, and not forgetting the marked results of man's unconscious selection, it seems to me almost certain that if the individuals of one sex were during a long series of generations to prefer pair- |