| OCR Text |

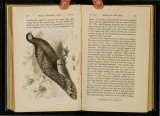

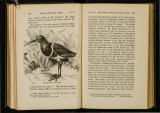

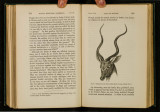

Show 154 SEXUAL SELECTION : BIRDS. PART JJ. CHAPTER XV. limns-continued. Discussion why the males alone of some species, and both sexes of other species, arc brightly coloured- On sexually-limited inheritance, as applied to various structures and to brightlycoloured plumage-Nidification in relation to colour- Loss of nuptial plumage during the winter. WE have in this chapter to consider, why with many kinds of birds the female has not received the same ornaments as the male ; and why with many others, both sexes are equally, or almost equally, ornamented? In the following chapter we shall consider why in some few rare cases the female is more conspicuously coloured than the male. In my ' Origin of Species ' 1 I briefly suggested that the long tail of the peacock would be inconvenient, and the conspicuous black colour of the male capercailzie dangerous, to the female during the period of incubation; and consequently that the transmission of these characters from the male to tho female offspring had been checked through natural selection. I still think that this may have occurred in some few instances: but after mature reflection on aU tho facts which I have been able to collect, I am now inclined to believe that when the sexes differ, the successive variations have generally been from the first limited in their transmission to the same sex in which they first appeared. Since my remarks appeared, the subject of sexual coloration 1 Fourth edition, 1866, p. 241. .CnAI'. XV. SEXUALLY-LIMITED INHERITANCE. 155 has been discussed in some very interesting papers by Mr. Wallace,2 who believes that in almost all cases the successive variations tended at first to be transmitted equally to both sexes; but that the female was saved, through natural selection, from acquiriug the conspicu- ous colours of the male, owing to the danger which she would thus have incurred during incubation. This view necessitates a tedious discussion on a difficult point, namely whether the transmission of a character, which is at first inherited by both sexes, can be subsequently limited in its transmission, by means of selection, to one sex alone. We must bear in mind, as shewn in the preliminary chapter on sexual Relection, that characters which are limited in their development to one sex are always latent in the other. An imaginary illustration will best aid us in seeing the difficulty of the case : we may suppose that a fancier wished to make a breed of pigeons, in which ihe males alone should be coloured of a pale blue, whilst the females retained their former slaty tint. As with pigeons characters of all kinds are usually transmitted to both sexes equally, the fancier would have to try to convert this latter form of inheritance into sexually-limited transmission. All that he could do would be to persevere in selecting every male pigeon which was in the least degree of a paler blue ; and the natural result of this process, if steadily carried on for a long time, and if the pale variations were strongly inherited or often recurred, would be to make his whole stock of a lighter blue. But our fancier would be compelled to match, generation after generation, his pale blue males with slaty females, for he wishes to keep the 2 'Westminster Review,' July, 1867. 'Journal of Travel,' vol. i. 1868, p. 73. |