| Title |

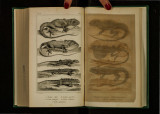

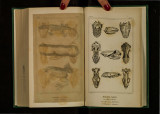

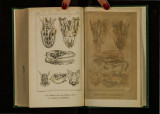

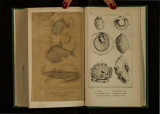

Animal Kingdom V.2 |

| Call Number |

QL45 .C945 1831; Record ID 9999430102001 |

| Date |

1831 |

| Description |

Cuvier, Georges (1796-1832). The animal kingdom, arranged in conformity with its...New York: G. & C. & H. Carvill, 1831 First English edition QL45 C945 1831 |

| Creator |

Cuvier, Georges, 1796-1832 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Latrielle, P.A. (Pierre Andre), 1762-1833); M'Murtrie, Henry, 1796-1865;Zoology |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XQL45C9451831v.2.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

Digital Image © Copyright 2013, University of Utah. All rights Reserved. |

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tiffs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s64b3tkw |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

288408 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s64b3tkw |