| Title |

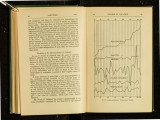

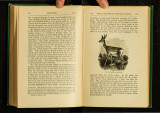

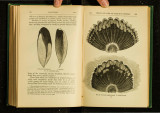

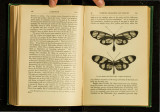

Darwinism: An Exposition of the Theory of Natural... |

| Call Number |

QH366 .W2 1889; Record ID 99811150102001 |

| Date |

1889 |

| Description |

Wallace, Alfred Russel (1823-1913). Darwinism: An exposition of the theory of natural...London, New York: Macmillan and Co., 1889 First edition QH336 W2 1889 University of Utah copy inscribed "July - 1889 J.C.F Grumbine |

| Creator |

Wallace, Alfred Russel, 1823-1913 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Evolution; Natural selection |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XQH366W21889.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tifs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobad ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6r2493m |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

283981 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6r2493m |