| OCR Text |

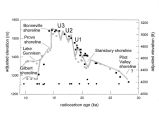

Show shorelines, the local algal bioherms, and the geodynamic highlights of this area as the centroid of Lake Bonneville hydro- isostatic deflection in a discussion led by Bruce Bills. As everyone will have gathered by now, one of the key questions in Bonneville basin aquatic system history has to do with the nature of the transition from deep- water Lake Bonneville to shallow- water Great Salt Lake. Certainly it was related to the transition from the last glacial maximum to the subsequent postglacial ( from Pleistocene to Holocene, from Oxygen Isotope Stage 2 to Oxygen Isotope Stage 1, the terminal Pleistocene megawarming, etc....). In the Bonneville basin, and probably in many other regions, this is really a set of questions that involves details of chronology and possible technologies for improving temporal resolution, details of rates of change and possibilities of very abrupt climate change, details of climatic extremes, details of the atmospheric general circulation that drove basin hydrologic responses, and details of oceanic general circulation that may have played a distant but momentous forcing role. In the field and in the laboratory, perhaps the most important questions revolve around evidence and its interpretation- what are we really looking at, what are we really seeing? For purposes of discussion, and for want of other explicit models, the following two pages depict models of late Plesitocene- Holocene change that may be relevant. ( Madsen on Lakeside Cave) Lakeside Cave contains evidence of a unique lake- margin foraging strategy employed by early Great Basin hunter- gatherers. Intermittently, throughout the 5000- year human occupation of the cave, people relied almost exclusively on grasshoppers as a food resource. The salted and sun- dried hoppers were collected from windrows washed up on the oolitic sand beaches which front the cave. Brought into the cave, the hoppers were apparently sifted from the beach sands, leaving layers of almost pure sand between the vegetal remains that comprise the bulk of the cave deposits. Dried human fecal remains suggest the hoppers were consumed directly, with little or no preparation. Hoppers contain over 3000 calories/ kg, and collecting experiments indicate they can be collected from the 0.2- m x 1.5- m x 15- km windrows at rates of 50,000 to 250,000 calories/ hr. These rates are much higher than those for any other measured resource, including large game animals; faunal evidence from the cave suggests hunting was much reduced when grasshoppers were available. ( Madsen on Homestead Cave) The deposits of Homestead Cave span the last 11,300 years and contain a stratified small- vertebrate record derived largely from owl pellets. Dating is controlled by 22 14C dates run primarily on woodrat fecal pellets. The early portion of the record contains an array of Lake Bonneville fish, including Bonneville Cisco ( Prosopium gemmifer), Bonneville whitefish ( Prosopium spilonotus), Bear Lake sculpin ( Cottus extensus), Utah chub ( Gila atraria), Utah sucker ( Catostomus ardens), and cutthroat trout ( Oncorhynchus clarki). Analyses of ^ Sr/^ Sr ratios from the Homestead Cave fishes suggest they were derived from a low- elevation lake slightly lower than the Gilbert level and probably represent a massive die- off associated with a regressive phase of Lake Bonneville immediately prior to the Younger Dryas. The presence of small mammals such as marmots ( Marmota flaviventris), bushy- tailed woodrats ( Neotoma cinerea), and pygmy rabbits ( Brachylagus idahoensis), and birds such as woodpeckers, together with ratios of chisel- toothed and Ord's kangaroo rats, from the lower levels of the cave suggest the early Holocene ( 10- 8 ka) was both cooler and moister than at present, with big sage ( Artemisia tridentata) dominating open areas and trees growing along now- dry water courses. |