| OCR Text |

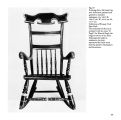

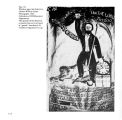

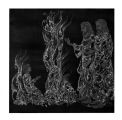

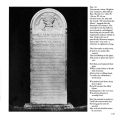

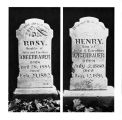

Show Fig. 140 Gravestone rubbing, Sarah C. Heaton stone. Payson Cemetery. A. H. Child. White marble (original). 1907. H: 102.5 cm. W: 45.0 cm. Collection of Utah Arts Council. The weeping willow, a traditional symbol of mourning and death, is used in combination with stars representative of the heavens. The rope, which follows the perimeter and divides the stone into sections, symbolizes eternity. The epitaph on the base of the monument is also of traditional origin. (Rubbing by Maury Haseltine and Martha Schack) Fig. 141 Gravestone rubbing, Barbara Stucki Reber stone. Santa Clara Cemetery. Tan sandstone (original). 1895. H: 115.0 cm. W: 47.5 cm. Collection of Utah Arts Council. This large sandstone marker from southern Utah provides an exquisite example of folk art. The primitive dove-and-flower arrangement is beautiful in its strength and simplicity, as is the lettering. The partly deteriorated verse reads as follows: Rest sweet in pease untill you Come forth in the morning of The First Resurrection some kind of personal image about the departed-it is best described as a legend. Finally, there is often below the body of the stone a base on which is inscribed a postscript, a couplet or quatrain of poetry or a proverbial saying acting as a kind of counterbalance, in both a symbolic and a graphic sense, to the canopy. The function of this epitaph is most often a message of comfort and hope to the survivors or a tribute to the deceased (Figs. 142 [drawing] and 143). Almost everything placed upon a gravestone beyond the vita itself has symbolic meaning-which is to say that there is always more there than meets the eye. A dove in flight with a rosebud in its beak occupying a medallion on the gravestone of a girl who died at age nineteen evokes a two-fold analogy: The rosebud symbolizes the physical embodiment of the girl; the dove represents the girl's soul in flight to heaven, or else a heavenly messenger carrying the girl's soul away or announcing that it has departed. A dove with a broken wing lying against a stump must be man himself, incarnate and dying, as in its time every living being dies. To "read" a gravestone, then, requires the acquisition of knowledge of symbolic forms and of their particular use at any given time in history and on a particular stone-in effect, in their context. It is helpful to know the traditional role of doves, for instance, in ballads, myths, legends, rites, and ceremonies of one's own and other related ethnic groups. All the forms appearing on gravestones have, or should have, symbolic overtones that emit messages of life and death (Fig. 144); of burial and resurrection; of peace and rest (Fig. 145); of separation and reunion; and of man's bond with God, nature, the cosmos, and especially mankind. These symbolic meanings have two sources: tradition, or the ways in which that image has served among generations past; or the company that it keeps on a particular gravestone. Symbolic forms are typically of ancient origin, are stable and traditional within the ethnic group, and more often than not are shared by other ethnic groups that ascribe to them similar but not identical meanings. Many of them spring from ancient human beliefs: stumps, tree trunks, and cut logs that represent the basic stirrings of life; vines, tendrils, ivy, and weeping willows; parasitic or deciduous trees or plants that deny man the life-sustaining substances of sunlight and air. Gravestone art is expected to be conservative. For the monument on the graves of ancestors one is apt to choose the most traditional images. There are two forces which operate to change this principle and to bring into use new images when they do appear: the weakening of the symbolic powers of traditional images, and the substitution of wholly new images because new experiences of a tremendously changing nature have brought them into being. 141 |