| OCR Text |

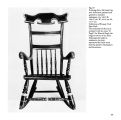

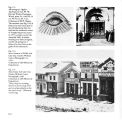

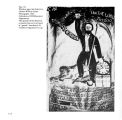

Show lasses, and soft soap. There was no regular pay day, but whenever a man required anything, I gave him an order on certain tradesmen with whom I kept a credit account for the purpose and paying the amount, by exchange of my goods.x x During the years from 1850 to 1870 furniture makers throughout the territory conducted business in a similar manner. Many worked alone in their own small shops; others operated small factories, often connected with lumber mills, where they employed a number of workmen. By 1870 there were approximately fifty cabinetmakers, chairmakers, carvers, and turners working in Salt Lake City, then a city of 12,000 people.12 The furniture made in these shops was essentially conservative in form and style, relying heavily on simplified versions of the neoclassical Sheraton and Empire styles of the early nineteenth century. Traditional slat-back and Windsor chairs were also common. The interpretation of these styles in softwood, however, possessed a distinctive boldness and vigor. Most pioneer furniture was further enriched with painted and grained decoration-that is, it was painted in the popular country furniture tradition to simulate colorful hardwood grains (Figs. 63-70, 73, and 74). Surviving Empire gondola chairs made in the Public Works shop in 1856 attest to the stylish production of this Church-sponsored shop (Fig. 71). The Public Works was Brigham Young's scheme for putting immigrant craftsmen to work as soon as they arrived, thus providing them with means to support their families (Fig. 72). Carpenters and joiners were paid or credited with $2 per day,13 and in addition to their work on Church and public projects they had many private customers. The Public Works accounts show that in 1852 the carpentry shop made, among many other things, a trundle bed and breakfast table for Brigham Young and two tall desks for the tithing office. They also made cradles, churns, clock stands, adobe molds, and cupboards for private customers, as well as making furniture repairs of all sorts.14 In the 1860s the Church sponsored cooperative associations of cabinetmakers and other craftsmen for the purpose of bringing together their capital and experience to help make home-manufactured articles competitive with imported goods. During the 1870s cooperative ventures-such as the Zion's Cooperative Mercantile Institutions, United Orders, and Boards of Trade-were organized by Church leaders in many communities. The Parowan United Manufacturing Institution included a co-op store, a tannery, a shoe and harness shop, a lumber mill, and a cabinet shop (Fig. 77). Thomas Durham, an English craftsman who immigrated to Utah in 1856, was the foreman of the cabinet shop (Fig. 76). For a while during the 1870s P.U.M.I. prospered, and its dis- 72 Fig. 69 Bureau. Payson. Attributed to Walter Huish. Softwood, painted and grained to simulate mahogany. Ca. 1870. H: 105 cm. W: 98.75 cm. D: 50 cm. Collection of Pioneer Trail State Park. The construction of this simple case shows some refinement in the moulded top and in the beaded drawer dividers, which are actually extensions of the drawer fronts. The graining of the drawer fronts to simulate crotch mahogany veneer is an attempt at sophisticated decoration. Fig. 70 Flour bin. Brigham City. Softwood, painted and grained to simulate walnut and burled walnut panels. Ca. 1870. H: 90 cm. W: 90 cm. D: 52.5 cm. Collection of Pioneer Trail State Park. Original owners of the flour bin were William and Mary Jordan Evans, emigrants from the Welsh coal mines to Brigham City in 1865. |