| Title |

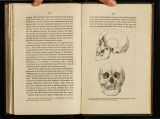

Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature |

| Call Number |

QH368 .H96; Record ID 99118020102001 |

| Date |

1863 |

| Description |

Huxley, Thomas Henry (1825-1895). Evidence as to man's place in nature. London, Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate, 1863 First edition QH368 H96 |

| Creator |

Huxley, Thomas Henry, 1825-1895 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Human Beings - Origin |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

Q111.H3_Box71.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tifs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page PDF. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s65f21hf |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

281136 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s65f21hf |