| Title |

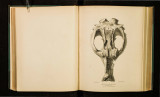

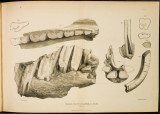

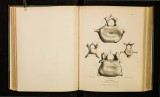

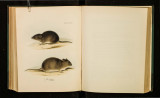

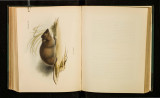

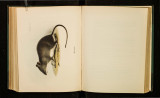

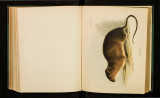

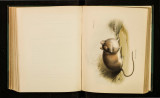

Zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, under the command of Captain Fitzroy, R.N., during the years 1832 to 1836, v.1 |

| Call Number |

QL5 .B3; Record ID 9996160102001 |

| Date |

1839 |

| Description |

Darwin, Charles (1809-1882). Zoology of the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, under the...London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1839-43 |

| Creator |

Charles Darwin, 1809-1882 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Beagle Expedition (1831-1836); Bell, Thomas, 1792-1880; Blomefield, Leonard, originally Leonard Jenyns, 1800-1893; Eyton, Thomas Campbell, 1809-1880; Gould, John, 1804-1892; Great Britain. Treasury; Owen, Richard, 1804-1892; Waterhouse, G.R. (George Robert), 1810-1888;Zoology |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

XQL5B3v.1.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Cedar Gonzalez |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 400 ppi tiffs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 4 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6jh51j4 |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

286865 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6jh51j4 |