| Title |

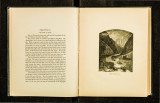

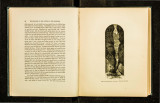

Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries Explored in 1869, 1870, 1871, and 1872, Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution |

| Call Number |

F788 .S65 1875; Record ID 9914767210102001 |

| Date |

1875 |

| Description |

Pt. 1. History of the explorations of the canyons of the Colorado [May 24-Sept. 20, 1869] Report on a trip to the mouth of the Dirty Devil River [May 27-July 11, 1872] by A.H. Thompson.--pt. 2. On the physical features of the valley of the Colorado.--pt. 3. Zoology: Abstracts of results of a study of the genera Geomys and Thomomys, by Elliott Coues. Addendum A. The cranial and dental characters of Geomydæ, by Elliott Coues. Addendum B. Notes on the salamander of Florida (Geomys Tueza) by G.B. Goode.; 291 pages, 80 unnumbered leaves of plates : illustrations, folded map ; 30 cm |

| Creator |

Powell, John Wesley, 1834-1902 |

| Publisher |

Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Subject |

Powell, John Wesley, 1834-1902. Report on the exploration of the Colorado River of the West and its tributaries; Powell, John Wesley, 1834-1902--Travel--Colorado River (Colo.-Mexico); Colorado River (Colo.-Mexico)--Description and travel |

| Contributors |

Goode, G. Brown (George Brown), 1851-1896; Coues, Elliott, 1842-1899; Thompson, A. H. (Almon Harris), 1839-1906 |

| Source Physical Dimensions |

291 pages, 80 unnumbered leaves of plates : illustrations, folded map; 30 cm |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Identifier |

F788-_S65-1875.pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

|

| Scanning Technician |

Ellen Moffatt |

| Digitization Specifications |

Original scanned with Hasselblad H2D 39 megapixel digital camera and saved as 600 ppi tiffs. Display images created in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom 5 and generated in Adobe Acrobat ProX as multiple page pdf. |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s6253kj6 |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

308244 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6253kj6 |