| Title |

Pathological anatomy, pathology and physical diagnosis. : A series of clinical reports comprising the principal diseases of the human body: Volume 1 |

| Call Number |

RB33 .J4; Record ID 9934641670102001 |

| Date |

1883 |

| Description |

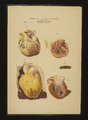

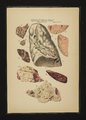

Born in Cabrai, France, John Allard Jeancon was educated in Paris, Turin, and Berlin before being graduated with a medical degree from the Royal College of Surgeons at Edinburgh in 1854. He immigrated to the United States, where, in 1854, he began teaching at the Eclectic Medical Institute (EMI) in Cincinnati, Ohio. He served as a surgeon in the 32nd Regiment of Indiana Volunteers during the Civil War. While serving, he, along with other surgeons and the United States Surgeon-General, protested the indiscriminate use of mercury as a drug by the army, eventually leading to its ban. After the war, he returned to EMI until he retired in 1891. Pathological Anatomy contains case studies of patients, with full-color plates of pathological ailments. Issued in twenty-five parts, sold as a whole. This scan includes the index and parts 1-3 and 8-10 |

| Creator |

Jeançon, J. A. (John A.) |

| Subject |

Anatomy, Pathological--Atlases; Diagnosis; Clinical medicine |

| Type |

Text |

| Format |

application/pdf |

| Language |

eng |

| Collection Name |

Rare Books Collection |

| Holding Institution |

Rare Books Division, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah |

| Rights |

https://rightsstatements.org/page/NoC-US/1.0/ |

| Scanning Technician |

Natalia Soto |

| ARK |

ark:/87278/s62z5jbs |

| Setname |

uum_rbc |

| ID |

1402011 |

| Reference URL |

https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s62z5jbs |