| OCR Text |

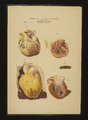

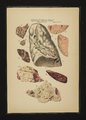

Show DISFASES OF THE ()RGANS ()F RESPIRATION. Tamas Y1 II. EmboficPneumonia. lafm‘ct info I/Ic Lung Tissue. Ste- nos/s of Left rl/Iricu/o- '1 hdriculur Opening, with 1/1/- jun'l‘rop/u/ of I‘l/c Left lvt‘ilfl'I-(‘fla (‘.\sI‘:.-.\ woman 41- years of age. ,[l/s/oi'f/.-l lad frequently very violent palpitation ofthc heart, lasting several days; experienced constantly in the region of the heart a sense of oppression and suffocation; was repeatedly attacked with hzemopt'ysis. Com/ition. mu] syn/prams f/nwa (ll/gs- before death-Face purple; expect'orates clear blood,which is sometimes bright red, sometimes dark colored; very hurried breathing, but claims not to feel oppressed; is able to sp1ak audibly; pulse almost gone; beyond some moist rale in the bronchi. nothing very abnormal in the lungs; beating of the heart very tumultuous, yet without murmur. Is gradually overcome. by Weakness; coma; involuntary discharges; dies from suffocation. Post JIortmn.-l hemorrhagic infarcts disseminated throughout both lungs, some very extensive. some small (Figs. 2, 3). They were irregularly spheroid and distinctly irritant detritus in its cavity; and when the watery portion of this dead mass is absorbed by imbibation, a central caseous debris will remain. Gaseous degeneration in small»celled hepatization is produced by the anaemia caused by the over-filled air cells with these elements. For, no circulation can take place when the vessels are compressed. The small cells are of a triple origin: 1. From the endothelium of the vessels. 2. From the blood in the artery. 3. From the internal coat and the vasa vasorum.-(Frz'edlmulcr). St'ange as it may appear, that the cells should be derived from the cavity of a vcssel,whilst the blood is in a state of circulation, yet Bit/mop" has clearly demonstrated that migratory cells pass from the cavity of arteries, through their walls, outside; and Sariul'lc has also seen those migratory cells enter capillaries whilst blood was in full circulation within them. \Vhere vessels are thus affected, they become unfit for nutrition of tissues. \thn cascation has once taken place. it may remain in the tissue a long while without undergoing any change. (This will often prevent differential diagnosis between acute and chronic catarrhal inflammation.) Rimlflcisch considers the caseous state as a pathognomic sign of the chronic form. The older patholog .fts have taken this caseous condition as a form of pulmonary phthisis. Although this is not tuberculosis, it is a state from which tuber- culosis may readily develop; but it does not always do so. (‘aseous masses ditfcr, in the lungs, in color and consistence, according to the mode of their production. The dry form isyellowish white, tough, slightly transparent and constitutes a form of coagulating mortitication. This is usually found in the proximityof the smaller bronchi. A thorough cascous mas is always withouta nucleus, sometimes perfectly homogeneous, sometimes slightly granular. The homogeneous often passes into the granular form. The soft. variety is white, and consists of a fatty albuminous detritus. Both forms may exist by the side of one another, orthc solid variety may pass into the soft. The filial termination of a caseous focus is either Colte'quation and eventual absorption, or transformation into a calcareous mass. The lime in this is generally united with albumen; when decomposition takes place the albumen is eliminated, and a very brittle chalky mass is left. Acute catarrhal pneumonia clinically differs from its chronic form only in extent and not. in kind, for both have the same anatomical basis; and this is inflammatory or irritative alteration of the mucous membrane of the bronchiols. They both have hyperiemia and oedema of the tissue for a beginning, and both may be considered primarily as bronchiolitis. It only depends on concomitant circumstances to assume the one or the other form. In both there is alteration in'the cavity and wall of the bronchi and bronchiols, also in the pulmonic tissue proper. When the muco-purulent secretion stagnatcs in the bronchial tubes, it becomes gradually inspissatcd, its cellular elements undergo molecular death, and the whole constitutes a yellowish white softish nodule, indicating the former cavity of the tubes which are now converted into solid cylinders. Such a condition can but cause excessive irritation to the bronchial wall, and, sooner or later, reactive phenomena of its tissue will become manifest in the mucous membrane at first, in its other structures subsequently. The peribronchial tissue will undergo a kind of callous indurative Change, after the progressive hyperplastic processes of inflamma- tion have involved the tissue proper of the tubes. Such thickened and filled small bronchial tubules will present the appearance of solid nodules, which Were formerly held to be tubercles. The thickening of the pcribronchial tissue is associated with a similar condition of the interlobular connective tissue, its immediate continuation. The accumulated secretion Inay become so abundant as to dilate parts of the smaller bronchial branchlets and to attenuate their walls by pressure and atrophy. "'hen a number of branches of the bronchi are thus partly closed up and dilated, the inspired air will have a tendency to dilate the still open portions of the respiratory organs, and permanent dilatation may thereb)' be broduced. This (ctatic condition must not be. con- founded with the highly hypcrplastic and widened bronchi found in common catarrhal bronchicctasis. In the broiicl1opneumonic ectasis only the mucous membrane retains more or less its normal character; the other tissues of the tube are exceedingly atro- phied. More especially do the blood vessels partake of this atro- 1 [SECTION III. circumscribed, their black color contrasted with the lighter coloredsurroundings. The greatest number of the infarcts were immediately below the pleura, which they raised in several places; they presented a friable, granular appearance. aml seemed to have obliteratedall the air cells. some of which were torn by the massive effusion of the blood. The lower lobe of the right lung looked like one affected with fibrinons pneumonia; it was yellowish, red and gran111:1r. but offered that difference, that it was highly compact and did not crcpitate. There was hypertrophy of the left ventricle and stricture of the auriculo-ventricular open- ing of the same side to a marked degree. Flo. l. )lelanotie pneumonia and anthracosis over a large portion of the outer surface, and within the lung, of a man who worked in a coal mine. The particles of coal- dust had mingled with a quantity ofpulmonic pigment, and formed circular spots immediately below the pleura. There were a number of fibrinous deposits upon the membrane. in the shape of'strings and circularspots,somc ofwhich looked gray. others white. The interlobular tissue was hypertrophied and plainly marked the interlobular boundaries. phic condition. The catarrhal secretion abounds in cellular elements and contains but little liquid, and is firmly attached to the wall of the tube in little heaps. Eventually the mucous membrane mav 11n- dergo the process of ulceration of a highly destructive nature: and *ause extensive excoriation of its layers. Frequently tuberculous matter is found in such ulcerated tissue. "Then such astate of the bronchial tissue continues for any length of time, or when the ul- ccrative process is repeatedly reproduced, destructive action extends to the pulmonic parcnc11yma,which is generally by this time already unable to perform its function of renewal of air, and formation of more or less extensive cavities begins. The effect of the closed bronchi upon the hing tissue-besides the histological changes it superinduccs,as described before-is the formation of a condition similar to f(etal atelcctasis. The infundibulabecome contracted, the air cells shrink, and the parts situated on the outer surface become uneven. The shrinking of the air cells necessarily brings the blood vessels closer to each other, and this gradually superinduces a. permanent hyperainiia of the parts. Sooner or later this hyperzemia produces exudativc (edema in the now shrunk tis- sue. This serous infiltration once more swells the tissue up, but makes it soft and very compressible. Outside it has a bluish color: on a cut surface the color is deep reddish brown, moist and smooth, and resembles very much the pulp ofthc spleen. It has received the name of splenisation. Such splenisation always indicates a low heart power; 'sociatcd with static hyperannia and serous infil- trates in th 3 airless alveoli. A state like the one just described may terminate in two ways: Either in 1rctcr<lfc ardcma or {fray '1'11d1o'at1'o/1. The first differs from a splcnoid state, that no hyperzemia can take place in the now exceedingly infiltrated tissue, which seems impermeable to the solider portions of the blood. This seeks new channels in more yielding portions of the structure. The (:edomatous tissue looks pale or slightly rose 00101‘.~(Sec. III, Tab. X, Fig. 2, L. S.) From a cut surface of such a lung, a clear, highly concentrated serum, containing yellowish white particles, oozes out. Under the microscope the particles prove to be fatty degenerated cells, col- lected in minute nodules. The surrounding hyperzemic. tissue strongly contrasts with the pale structure. (hi1yinduration is regularly found in the above described chronic periln‘onchitis, which is ever connected with an inflammatory hy- perplasia of the interlolmlar septa. These become the most prominent part of the otherwise atrophied parenchyma. The air cells are nearly empty, or altogether w1pcd out by the. neoplastic interstitial tissue. ()nly theintcrlolmlar vessels are still to some extent permeable. The gray or blackish blue color is due to collections of black pulmonic pigment, which is found in variable quantities in its different portions. (Sec. III, Tab. VIII. Fig. 1, Sec. III, Tab. IX, Fig. l, i1[.P.P., Fi '. 2, 3, L. S.) Originally the pigment constituted the remnant of exceedingly numerous minute hzemorrhagic collections. Mingled with these are great numbers of particles of coal dust or soot inhaled and deposited in the tissue (Sec. III, Tab. X, Figs. 1, 2, 5). Ultimate Changes of Gaseous 11108868. The greater the volume and the quicker the formation of cascous masses, the sooner dothey undergo retrogressive change, which always begins in the center of a 111i :s. By attraction of water from its periphery, it softens, turns into a pus-like, flocculent, semi-solid substance. When corrosive inflammation has preceded the soften- ing, which happens most frequently in dilated bronchi,clogged up with stagnant masses of sccretion,etc., the parcnchymatousas well as the bronchial tissue will become disintegrated and cavities will form. The cavities will generally contain exceedingly corrosive substances, which, when they pass through any orifice formed into a bronchial tube, form coiInnunications with the outer air. l'utrefacfive agencies soon penetrate such cavities, and convert the greatest portion of their contents into exceedingly putrid material. These are generally expectoratcd as highly offensive sputa.containing reinnants of pulmonic and bronchial tissues, in all stages of decay. As long as such sputa are. thrown out, that long we may be sure. that a cavity or cavities are extending, fortliey are the debris of destruction ofthcir walls. l'hiparative process in an infiltrated casc- ous tissue can only take place after {/10 (Icmleum'ous mass has been eliminated or changed, chemically, into an inert substance. |