| Description |

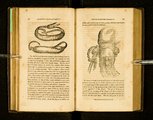

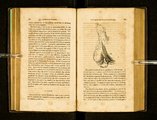

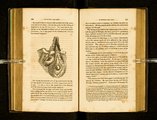

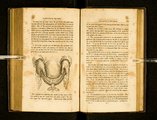

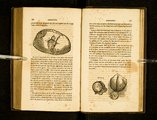

Charles Bell, born in Edinburgh, was a surgeon who served with the British Army at the Battle of Waterloo. In 1767, Bell took over the school of anatomy in Great Windmill Street, founded by William Hunter that same year. A professor of surgery at the University of Edinburgh, he is best known for his medical illustration and for his pioneering study of the human nervous system. He accurately described the thoracic nerve, or, "Bell's nerve;" he discovered that a lesion of the seventh facial nerve causes paralysis, "Bell's palsy;" and he demonstrated the function of spinal nerves, i.e. that motor function relates to anterior roots and sensory function relates to dorsal roots, the "Bell-Magendie law." In 1807, Bell published his System of Operative Surgery, where he described surgical operations based on personal experience. As an appendix to this work, Bell added an essay on gun-shot wounds, based on knowledge he acquired as a surgeon for the wounded of Waterloo. |