|

|

Title | Collection Number And Name | Photo Number |

| 1 |

|

On this Land-Sat photo of the State of Utah, heavily vegetated areas are red, unvegetated areas are light colored, and bodies of water are dark blue. Notice three prominent landforms: Great Salt Lake, the east-west aligned Uinta Mountains in the northeast corner of the state, and the San Rafael Swell in the eastcentral area. (May 1984) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n001 |

| 2 |

|

A geologic map of Utah, illustrates the strata conventionally colored differently according to geological age. Notice the San Rafael Swell, the dominant geologic and geographic feature in the eastcentral part of the State. The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry (C-LDQ) is located on the northern end or nose of the Swell. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n002 |

| 3 |

|

This view of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry (C-LDQ) in Emery County, Utah is typical of the primitive landscape and isolated areas, where many of Utah's dinosaurs are found and collected. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n003 |

| 4 |

|

These colorful, Morrison Formation exposures are similar to the rock outcrops where dinosaur bones are found in many localities across the Colorado Plateau of Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n004 |

| 5 |

|

The C-LDQ Visitor Center was constructed in 1967 by the Castle Valley Job Corps in collaboration with the Price River Resource Area of the Bureau of Land Management, and the College of Eastern Utah, Prehistoric Museum in Price City. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n005 |

| 6 |

|

The Visitor Center at the C-LDQ, which became a United States Natural Landmark in 1968, has some interesting graphics that interpret and detail the operation and history of the Quarry. Included in the exhibits are some prepared, original dinosaur bones, and a mounted free- standing skeleton of a medium-sized Allosaur, which consists of less than 50% of the original, fossil bones. The skull of the Allosaur can be seen through the window in the front of the building. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n006 |

| 7 |

|

Interior of the C-LDQ Visitor's Center showing a dinosaur skeleton. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n006a |

| 8 |

|

This is a view of the main interpretive exhibit, an Allosaurus, inside the Visitor Center at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. The Center is open on a limited basis during the summer months and not at all for the rest of the year. The Quarry, Visitor Center, and picnic areas are supervised and maintained by the United States, Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management with the support and excavation at various times of the College of Eastern Utah, Prehistoric Museum, the Earth Science Museum at Brigham Young University, and the Utah Museum of Natural History. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n007 |

| 9 |

|

This oil painting by Utah artist, Gale Hammond, is his interpretation of dinosaur life at the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry 147.5 million years ago. A large Allosaur looks on, while a second predator attacks a Camptosaur. Notice the vegetation and a ponderous sauropod dinosaur wading the shallow lake in the background. Few dinosaur Paleontologists now agree that sauropods spent much time swimming or wading, thereby risking getting mired in the mud of or adjacent to shallow bodies of water. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n008 |

| 10 |

|

Dinosaur hunters often enjoy a camping experience, while prospecting for and collecting dinosaur bones, as seen here at the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. The Quarry was active and open full-time during the summers of 1960 through 1964. It has been worked sporadically during the past four decades; however, prior to that the first scientific collecting of record was done in 1927. The most intensive collecting was done during the summers of 1939-41 and 1960-64. (May 1960) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n009 |

| 11 |

|

Painting interpretation of dinosaur life. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n009a |

| 12 |

|

A large house trailer, seriously damaged traveling the rough road to the C-LDQ, was the solution to the housing problem the second year (1961) of the University of Utah Cooperative Dinosaur Project (UUCDP). (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n010 |

| 13 |

|

The last attempt at housing the C-LDQ field crew was a 16 foot square shack that boasted a gas stove and refrigerator, a table, four chairs, and two folding cots. (June 1962) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n011 |

| 14 |

|

In the early years, young visitors to the C-LDQ were allowed to dig in the spoil piles next to the excavation. (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n012 |

| 15 |

|

If the young prospectors were lucky and raised their hands when asked about their success, we would have them "donate" their significant finds to the collection. They were allowed to keep fragments of no scientific value. (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n013 |

| 16 |

|

A good lesson to learn early on, when digging dinosaurs, is that even in a desert there is occasional rain; and when it rains, it is advisable to have a drain in the lowest part of the quarry excavation lest it turn into a wading pool, as seen here. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n014 |

| 17 |

|

The steel buildings, assembled over the unexcavated Quarry surface in 1979, were an important addition; because they afforded protection from both vandalism and the weather. They were long overdue improvements making it no longer necessary to re-excavate the quarry at the beginning of the field season and then cover it again at the conclusion of work in the late summer. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n015 |

| 18 |

|

Prior to excavation the Quarry surface was carefully divided into a one yard grid system. Note the stakes and flags, which facilitated the precise mapping of each bone before its removal and transport to the laboratory at the University of Utah for preparation, curation, and eventual study. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n016 |

| 19 |

|

For nearly 20 years following the initial Quarry opening by the University of Utah Cooperative Dinosaur Project in 1960, it was necessary to open and close the Quarry with heavy equipment each field season to protect it from vandalism and illegal collecting. (October 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n017 |

| 20 |

|

The fossiliferous unit at the C-LDQ, which consists of poorly stratified to blocky, bentonitic shales, is overlain by a dense, hard, siliceous, freshwater limestone. The surface between the two units shows evidence of channeling as seen here. (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n018 |

| 21 |

|

Some fossil bones from the C-LDQ, such as this left premaxilla of Allosaurus, require minimal or no special preparation in the laboratory, but such is the exception rather than the rule. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n019 |

| 22 |

|

In numerical order, each fossil is cataloged, measured, identified, and carefully plotted on a base map before it is removed from the Quarry surface. This is just one part of the precise record keeping at the Quarry and compilation of the important data on the thousands of individual fossils exposed and collected there. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n020 |

| 23 |

|

This section of the composite Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry map illustrates the jumbled condition of bones, as they were at the time of burial. They appear as though the disarticulated parts of nearly six dozen dinosaurs had been stirred into a huge pot of mud and left to be found, unscrambled, and described by vertebrate paleontologists 147 million years later. Accurate maps and carefully written records are an essential part of dinosaur collecting and subsequent scientific research. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n021 |

| 24 |

|

These are fossil bones as discovered and uncovered in place at the Quarry. To one side are some of the tools used by the paleontologists who collect the fossils. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n022a |

| 25 |

|

Tools and supplies commonly used here are: ice-pick, brush,screwdriver, bayonet, broom, trowel, knee pads, scoop, glue, sample bags, insect spray, boxes, and tissue paper. Minimal preparation is done to facilitate collection in the field, but the careful, finish preparation on each bone is done only after the fossils have been carefully transported to the laboratory. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n022b |

| 26 |

|

When a fossil bone is prepared for removal from the Quarry in a plaster jacket, it is first uncovered and left supported on a narrow matrix pedestal. (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n023 |

| 27 |

|

Second, the more fragile and sometimes fractured fossil bones must be enclosed in a burlap and plaster jacket; which like the shell of an egg protects the contents so that each unit can be safely transported to the laboratory for final preparation and study. (June 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n024 |

| 28 |

|

These paired, pelvic bones of a large Allosaur are called pubes. They are shown here to illustrate the size of the circular opening at the top, which represents the maximum dimension of the oviduct or birth canal. It appears in this case to have been somewhat close to the diameter of a softball in size. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n025 |

| 29 |

|

This dorsal rib is singularly diagnostic of the presence of the rare theropod, Ceratosaurus in the C-LDQ, however, numerous other bones of this individual were found over the years. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n026 |

| 30 |

|

This is an exceptional occurrence of fossil bones in the Quarry, an articulated sequence of midcaudal vertebrae of Ceratosaurus. More commonly the fossil bones of a single individual are scattered over an area up to ten meters or more in diameter. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n027 |

| 31 |

|

This Allosaurus femur, the upper long bone of the hind leg, as found in place at the Quarry, shows displacement at mid-length. Apparently, this was the result of a small, reverse fault having an approximate displacement of about 12 centimeters. The movement occurred long after the enclosing sediments had become lithified, changed to limestone and shale. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n028 |

| 32 |

|

As an expedient and to minimize the necessary handling and preparation time; each bone, as practical, is wrapped, nested in paper excelsior, and boxed for transportation from the field to the laboratory. More fragile bones, regardless of size, require the conventional plaster and burlap packaging. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n029 |

| 33 |

|

This is another unusual series of articulated, caudal vertebrae. These bones belong to the uncommon Diplodocid, sauropod dinosaur, Barosaurus; which is represented as a solitary taxon in the C-LDQ. Single taxa are especially important in a mass burial situation like the C-LDQ, because they provide taphonomic data not available from the remains of multiple, but different sized individuals of the same dinosaur. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n030 |

| 34 |

|

A caudal vertebra (tail bone) of the sauropod dinosaur, Camarasaurus, as found in place at the Quarry. This particular dinosaur would have been about 55 feet long, almost 12 feet tall at the hips, and perhaps weighing more than fifteen tons in life. An original skeleton of this huge reptile is exhibited in a death pose at the College of Eastern Utah, Prehistoric Museum in the city of Price, Utah. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n031a |

| 35 |

|

A femur (thigh bone) of a Camarasaur illustrates the enormous size of this reptile. This bone, like most of the others in the Quarry, was found isolated rather than in close proximity to adjacent bones as they would appear with a complete, articulated skeleton. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n032 |

| 36 |

|

These are two unrelated bones in place. On the left is an ischium of Barosaurus and on the right an ilium of Allosaurus. (July 1961) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n033 |

| 37 |

|

Prior to mapping, each bone is carefully identified as to taxa (scientific name) and morphology (elemental name). | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n034 |

| 38 |

|

Most fossil bones are fractured, so must be coated with a preservative, as soon as they are uncovered and allowed to dry, to seal the fossil and fasten the numerous, tiny fragments in place. This step is necessary before the fossils can be safely removed and transported to the laboratory for final preparation and study. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n035 |

| 39 |

|

These students digging at the Quarry in 1976 are from Foothill Junior College near San Jose, California. They are learning first hand about the careful work required in collecting dinosaur bones. The Cleveland- Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry is often an important out-of-doors classroom for teaching the fundamentals of vertebrate paleontology and field collecting techniques. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n036 |

| 40 |

|

Any successful excavation of dinosaur bones requires a well-fed crew, and a well-fed crew requires a Master Chef; hence, Chef Pollardo in his field kitchen at the C-LDQ in the summer of 1976. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n037 |

| 41 |

|

Test holes were carefully dug by hand to determine the vertical and lateral dimension of the fossiliferous unit in the Quarry. Subsequently, drill holes confirmed the suspicion that the bones do not extend very far beyond the confines of the metal buildings that now cover and protect the Quarry. The buildings are an absolute necessity to protect the exposed fossils from both vandalism, the harsh winter weather of east-central Utah, and theft. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n038 |

| 42 |

|

This may appear to be a careful excavation for fossils. Pot-holing is not an acceptable quarrying procedure, because it complicates the collection of the fossils. Actually this is a test hole dug to determine the depth and extent of the fossiliferous horizon. (June 1960) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n039 |

| 43 |

|

During the 1960s at Fort Douglas, east of Salt Lake City, Utah was a World War II, army barracks, no longer standing on the upper University of Utah Campus, known as the "Bone Barn". It was the first "home" of the extensive bone inventory collected from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry. More than 60% of the original collection remained in Utah after the commitments to supporting institutions were met. These institutions had provided financial support for excavation, preparation, and research to the University of Utah Cooperative Dinosaur Project from 1960 to 1968. (June 1968) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n040 |

| 44 |

|

The most demanding step in the study of dinosaurs takes place in the preparation laboratory, where a single bone may require more than a hundred hours of intense work before it can be analyzed in detail. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n041 |

| 45 |

|

Much of the necessary preparation of fossil bones, as demonstrated on this premaxilla of Allosaurus, is done with a miniature air hammer called an AirScribe. The AirScribe is an indispensable tool in the careful preparation of most dinosaur bones. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n042 |

| 46 |

|

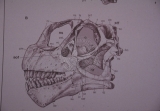

This composite of a medium-sized Allosaur skull required six months of work to fully prepare the fifty or more separate elements of the skull and mandible (lower jaw). It is now in the vertebrate fossil collections of the Utah Museum of Natural History on the University of Utah campus in Salt Lake City, Utah. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n043 |

| 47 |

|

Here is the backlighted braincase of Camarasaurus, which was projected at 2/3 natural size on a sheet of drawing paper. Next, a sketch would be made noting the complete outline and all features. This sketch would be used by the artist, as a basis for the illustration needed for a scientific publication. The sketch would be reduced 50% for a printed size of 1/3 scale. (May 1984) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n044 |

| 48 |

|

The fused caudal vertebrae and a chevron of Allosaurus show extensive pathology involving the transverse process of the right side. Traumas to the tails of dinosaurs are among the more common pathologies. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n045 |

| 49 |

|

Cast replicas are carefully made of each original bone to be displayed in this museum exhibit, which is seen here under preparation. Utilization of molds and casts allows the original bones to be completely accessible for study and unharmed by the drilling often needed to present them in a free-standing, mounted skeleton. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n046 |

| 50 |

|

There is a dramatic size range in the skeletons of the Cleveland-Lloyd Allosaurs. On the left are two claws from the forehand (manus), above on the right are premaxillae, tooth bearing bones of the upper jaw, and below caudal vertebrae from the distal third of the tail. The small vertebra is about two inches (five centimeters) long. The smallest Allosaur in the C-LDQ wasunder ten feet in length, the largest nearly thirty five feet long. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n047 |

| 51 |

|

This is the anterior end of the left dentary (lower jaw) of Ceratosaurus.It has two beautifully preserved teeth exposed showing the taxonomically characteristic, longitudinal grooves along the inner surfaces. Ceratosaurus is a rare, predatory dinosaur of the late Jurassic Period. There is only one of these flesh-eaters in the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry; however, at least five others are known from various Morrison Formation exposures in the Colorado Plateau and Wyoming. Ceratosaurus is also known from the Tendaguru beds of Tanzania in east Africa. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n048 |

| 52 |

|

This tooth of Allosaurus is representative of most theropods (carnivorous dinosaurs) in being sharply pointed and curved with serrate edges like the blade of a steak knife. These dinosaurs did not chew their food, but tore off large chunks of flesh and bone, which they swallowed whole. (May 1968) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n049 |

| 53 |

|

This is an accurate replica of the only egg discovered in the C-LD Q. It was found in a part of the quarry associated with a predominance of Allosaur bones and, very speculatively, is thought to be an egg of that most common genus in the C-LDQ. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n050 |

| 54 |

|

Notice the banded structure of this thin slice of fossilized bone. Studies are being made to determine the significance of the individual layers; which, if representing annulations or yearly growth rings, as seen in trees, might permit paleontologists to ascertain the age of an individual dinosaur. (May 1968) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n051 |

| 55 |

|

This thin-section of bone from an Allosaurus radius shows a classic alternation of lamellated annuli and non-lamellated zones, confirming the presence of true zonal bone in Allosaurus. Photo and slide were prepared and described by Researcher, Dr. Robin Reid. Magnification X 100. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n052 |

| 56 |

|

There were two episodes of mineral replacement or fossilization recorded in the Cleveland-Lloyd dinosaur bones: the first represented by an inner, white layer of sparry calcite lining the marrow cavity in this specimen and the second a layer of pale, amethyst quartz crystals that grew inward from the walls of cavities as seen in some geodes. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n053 |

| 57 |

|

This close-up of the rough surface of the bony core of a Stegosaur plate shows some of the numerous channels that indicate a rich blood supply. This is consistent with the belief that this animal was capable of thermoregulation, the control of its own body temperature by regulation of the blood flow through parts of the circulatory system. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n054 |

| 58 |

|

This sacrum of a Camarasaur is in the collections of the Earth Science Museum at Brigham Young University. It exhibits the same tooth mark pattern as noted on a similar bone complex collected from the C-LDQ. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n055 |

| 59 |

|

An unusually complete skull of a very large allosaur, originally collected at Dinosaur National Monument, is being prepared there by senior laboratory technician, Tobe Wilkens. There is cooperation and an ongoing exchange of ideas among the keepers and students of Utah's dinosaurs. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n057 |

| 60 |

|

The "Cliff Skull" of Camarasaurus at Dinosaur National Monument is an important part of a comprehensive head skeleton study of this interesting Morrison Formation sauropod. One of several scientific papers now being prepared for publication by dinosaur paleontologists currently studying Utah dinosaurs. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n058 |

| 61 |

|

Here is a scientific illustration of the skull of Camarasaurs lentus. Superior illustrations often are the most important part of a paper presenting a scientific description of a fossil bone, because they allow interpretation, not always possible, even with the best photographs. (March 1994) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n059 |

| 62 |

|

This pathological, fossil rib is representative of about 2% of the dinosaur bones from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, which exhibit anomalous conditions that record various kinds of disease or injury. Such bones are dramatic evidence that the dinosaurs suffered maladies and injuries similar to those of modern animals. (March 1994) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n060 |

| 63 |

|

An unusual node near the distal end of a sauropod rib has been thin- sectioned to determine the nature of the pathology. (July 1972) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n061 |

| 64 |

|

This original skull of Ceratosaurus magnicornis is of the type specimen collected west of Fruita, Colorado and described for publication by the Utah Geological Survey. (March 1977) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n062 |

| 65 |

|

Stokesosaurus, a recently discovered and described Utah dinosaur, to date known only from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry, has a peculiar ilium (hip bone) that exhibits a small, vertical ridge at midlength of the outer surface. Sometimes a single character, such as this, is the only clue to the identity of a particular dinosaur, which allows scientists to separate it from other similar types. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n064 |

| 66 |

|

This is the same left ilium of Stokesosaurus prepared and ready for study. (April 1972) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n065 |

| 67 |

|

The premaxillae of Marshosaurus to the left, and Stokesosaurus above, each with four teeth are compared with one of a very small Allosaurus to the right, which has alveoli for five teeth. Although all three of these dinosaurs were carnivorous, notice the difference in the shape of the tooth bearing bones. Similarly, if the teeth of each were present, they could be easily identified, one from another. (April 1972) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n066 |

| 68 |

|

A medial view of the premaxillae of a Marshosaur (left) with 4 teeth and Allosaur (right) with 5 teeth. These are important, taxonomic differences. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n067 |

| 69 |

|

This is a close-up photograph of a sample from the locality, where dinosaur "stomach contents" were described over three decades ago. Scientists now re-examining the site suspect that it may be a fairly large mat of fossilized vegetation, including wood fragments and seeds, and containing the bones of the sauropod dinosaur, Camarasaurus. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n068 |

| 70 |

|

Rarely, tiny dinosaur tracks, such as these, are recovered from the coal mines of Carbon and Emery Counties in east-central Utah. Dinosaur bones are usually found in one area or formation and tracks in another, but rarely are the two ever found together. Tridactyl (three-toed) tracks have been found in the rocky ledges above the C-LDQ horizon, but they were not in association with any fossil bones as found in the Quarry. One expert supposes that these tracks were made by a Stegosaur. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n069 |

| 71 |

|

Three-dimensional, life-size models are very popular in many dinosaur exhibits around the world. Among the best are those to be seen at the Utah Fieldhouse of Natural History, a museum in Vernal, Utah. Triceratops is seen in the foreground of this photograph taken shortly after a Utah winter snow storm. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n070 |

| 72 |

|

Another impressive, full-scale, life-like reproduction of a Morrison Formation dinosaur is the fiberglass model of Stegosaurus at Dinosaur National Monument near Jensen, Utah. The breathtaking Quarry exhibits of fossil bones exposed there are world famous and dinosaur paleontologists and tourists come from almost every country to see them. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n071 |

| 73 |

|

These chilly dinosaur models: Ceratosaurus, Stegosaurus, and a juvenile Camarasaurus are near the Main Street or south entrance of the Utah Fieldhouse of Natural History in the Vernal City Park. This is the work of Malin Foster, a Utah sculptor. They were unveiled in the 1950s and have stood well the test of time. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n072 |

| 74 |

|

This is the head skeleton and neck of Allosaurus presented in a formal garden setting by the generous lady who purchased the metal buildings, which now protect the C-LDQ excavation. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n073 |

| 75 |

|

A life-like reconstruction (Trophy Mount) by David Thomas of the head and shoulders of Allosaurus was prepared over a welded armature supporting exact casts of the original bones. The muscles, then the skin, were sculpted in turn to achieve a very life-like representation. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n074 |

| 76 |

|

A full scale model of this life-like Allosaurus may now be seen in one of Utah's Museums. This 1:24 bronze scale model and the life-size replica were done by sculptor, David Thomas. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n075 |

| 77 |

|

Full scale replicas of two Allosaurus sculpted by David Thomas, a well- known dinosaur artist who worked in Albuquerque, New Mexico. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n076 |

| 78 |

|

A full scale Pentaceratops is the companion bronze statue to Albertosaurus at the entrance of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History in Albuquerque. Pentaceratops is known from the Cretaceous formations of Alberta, Canada and New Mexico. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n077 |

| 79 |

|

This life-size restoration in bronze of Albertosaurus, a common flesh- eating dinosaur from the badlands of Alberta, Canada, was sculpted by David Thomas, a talented artist from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Albertosaurus is known from Utah by tracks and teeth collected from the coal mines in Carbon and Emery Counties, but as yet no bones have been found. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n078 |

| 80 |

|

A full scale model of Maiasaurus, the "Good Mother Dinosaur", by artist Dave Thomas, was commissioned by the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, MT. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n079 |

| 81 |

|

Dinosaur statuary by Utah artist, Gary Prazen, may be seen at the entrance to the College of Eastern Utah, Prehistoric Museum in Price City, Utah. The piece depicts dinosaurs "dining", but has been informally titled "Dinosaur love". | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n080 |

| 82 |

|

This fine mural was commissioned by the B.Y.U. Earth Science Museum and prepared by a noted Texas wildlife artist, Doris Tischler. The scene depicts the composite flora and fauna of Late Jurassic time in Utah as recorded in the sediments of the Morrison Formation from several Colorado Plateau localities. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n081 |

| 83 |

|

A poster attesting to the popularity of traveling dinosaur exhibits in Japan. The three digits on the manus suggest Allosaurus as the subject. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n082 |

| 84 |

|

A poster attesting to the popularity of traveling dinosaur exhibits in Japan. The three digits on the manus suggest Allosaurus as the subject. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n083 |

| 85 |

|

Three of the first mounted dinosaurs from the C-LDQ were displayed in 1968 at the opening of the new Utah Museum of Natural History. They are an Allosaurus attacking a Camptosaurus, while a second Allosaurus looks on. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n084 |

| 86 |

|

The cast skeleton of Diplodocus carnegii guarded the Dinosaur Garden at the Utah Fieldhouse of Natural History State Park in Vernal for nearly three decades. It was taken down, remodeled, and remolded in 1989. Now a new mount has been presented inside the UFNHSP. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n085 |

| 87 |

|

A death pose of an original, composite skeleton of Camarasaurus and Stegosaurus from the C-LDQ may be seen at the College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum in the city of Price, Utah. Two skeletons at CEUPM are mounted in a huge sandbox, an inexpensive exhibit, which allows easy access to the individual fossil bones for research or study. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n086 |

| 88 |

|

The disassembled, modular skeletons are easy to transport, as noted with this Allosaur being unloaded at Dinosaur National Monument. (October 1980) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n087 |

| 89 |

|

Tools and preassembled sections are laid out in the order of assembly prior to mounting. (October 1988) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n088 |

| 90 |

|

The entire mount is prepared in segments and modules that facilitate easy transportation, handling, and assembly. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n089 |

| 91 |

|

The sacrum and pelvic elements including the pubes, ischia, and ilia, are assembled first. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n090 |

| 92 |

|

Laying the entire skeleton out on the floor allows a last minute check for all parts to be at hand. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n091 |

| 93 |

|

Next the legs are fastened to the mounting deck of the exhibit. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n092 |

| 94 |

|

The articulated pelvic and sacral complex are then attached to the preassembled hind legs, which are shown fastened to the exhibit base. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n093 |

| 95 |

|

Next in the order of assembly, the dorsal (back) and caudal (tail) sections are attached to keep the mount in balance. (October 1988) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n094 |

| 96 |

|

The neck, ribs, chevrons, and forearms are fastened in place as one of the final steps in the assembly. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n095 |

| 97 |

|

The forearms are pinned in place after the dorsal ribs have been attached. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n096 |

| 98 |

|

The chevrons or haemal arches are attached to the wires installed between the caudal vertebrae during the early stages of construction. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n097 |

| 99 |

|

The last step is the touch-up of any nicks and scrapes sustained during transportation and mounting. (October 1988) | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n098 |

| 100 |

|

Installation of the skull is a two person job. | P1048 James H. Madsen Photograph Collection | P1048n099 |