| OCR Text |

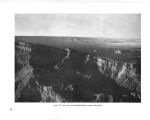

Show lustrations of the ability of northern zone plants of the higher mountain levels to survive in the lower zones, provided their moisture requirements are satisfied. Two or three miles southwest of Lyman's Reservoir, near St. Johns, Ariz., a small isolated cinder cone, grassy and otherwise devoid of trees, has on its shady north- facing slope a shallow steeply sloping ravine within the narrow confines of which there stands a slender file of ponderosa pine. Obviously a snowbank lingers in this shaded defile long after other snowTs are gone, thus providing moisture sufficient for the small colony, which is a mile or more from the main body of the forest and at a lower elevation. Similarly, countless mountain streams through the basin, long after descending from the cool highlands into the warm lowland valleys, are lined with pines and other mountain trees which, having been carried down as seeds, were able to establish themselves along the moist stream banks in the midst of an otherwise alien environment. Spectacular examples of climate extensions downward into a lower zone may be seen in the Canyon Lands of Utah. There the streams, upon leaving the mountains, frequently vanish into narrow, shadowy gorges of great depth which wind erratically for miles below the rolling surface of the sandstone mesas, on their way to join the canyon of the Colorado. The Transition Zone pines, in following these streams down from the mountain slopes, likewise disappear beneath the surface of the desert, and may be glimpsed only from the brink of one of these gorges or from an airplane. This reversal of the usual altitude relationships is well illustrated in Indian Creek and Montezuma Creek Canyons at the base of the Abajo Mountains, and similar examples occur over great areas of the basin, as on the Black Mesa, and at the edge of the Defiance and Mogollon Plateaus in Arizona. Likewise, the outlet streams of Boulder, Fremont, and other large lakes at the foot of the Wind River Mountains, in the Upper Green River Valley of Wyoming, carry long tongues of Boreal Zone lodgepole pines and aspens down through the treeless, grassy Transition Zone. Air currents.- Cold air tends to flow down canyons from the high peaks, especially at night, thus further promoting the downward migration of northern plants and animals along the stream banks. On the other hand, rising currents of warm air, especially those which sweep over mountain slopes from adjacent desert lands, have a reverse effect and carry the climate of the lower levels to a much higher elevation than usual. The Colorado River Basin contains countless examples of this upward shifting of the lower zones adjacent to desert areas. The Gila Mountains in southeastern Arizona exceed 6,000 feet and under other circumstances would be expected to have a Transition Zone pine forest at the summit. The heat of the San Simon Valley, however, carries the Upper Sonoran Zone to the summit of the range. A similar condition occurs, in varying degrees, in the Little San Bernardino Mountains north of the Salton Sea in California; in the Virgin Mountains of southern Nevada and northeastern Arizona; the Kaiparowits Plateau and San Rafael Swell in Utah; and in extensive foothill regions of the Green River Valley north of the town of Green River, Wyo. Mountain masses.- The larger the mountain mass, the greater the area of cool surface, and the less the likelihood of its being affected by the warming influences of surrounding lowlands. The great frigid mass of the Rocky Mountains, together with such lofty spurs as the San Miguel and Elk Mountains, and the White River Plateau, is able to maintain a Transition Zone climate at lower altitudes than can the isolated Henry and Abajo Mountains in southwestern Utah. A result of the proximity of mountain masses that is particularly noticeable in desert regions is the greater soil moisture at their bases derived from run- off. In the Colorado Desert, even in rainfall areas of 5 to 9 inches, many mountain barriers lifting up to 4,500 feet or more will knock out from 14 to 16 inches of rainfall per year . . . ( In) the Kofas . . . while they form a mountain island only 4,200 feet high . . . there is an increased run- off deriving from about 14 inches of rainfall per year, and this moisture, and the consequent food and cover that it produces, supports ( or did support before excessive hunting) a relatively abundant fauna of mule deer, sheep, quail and other forms of 13 |